Originally May 28, 2024.

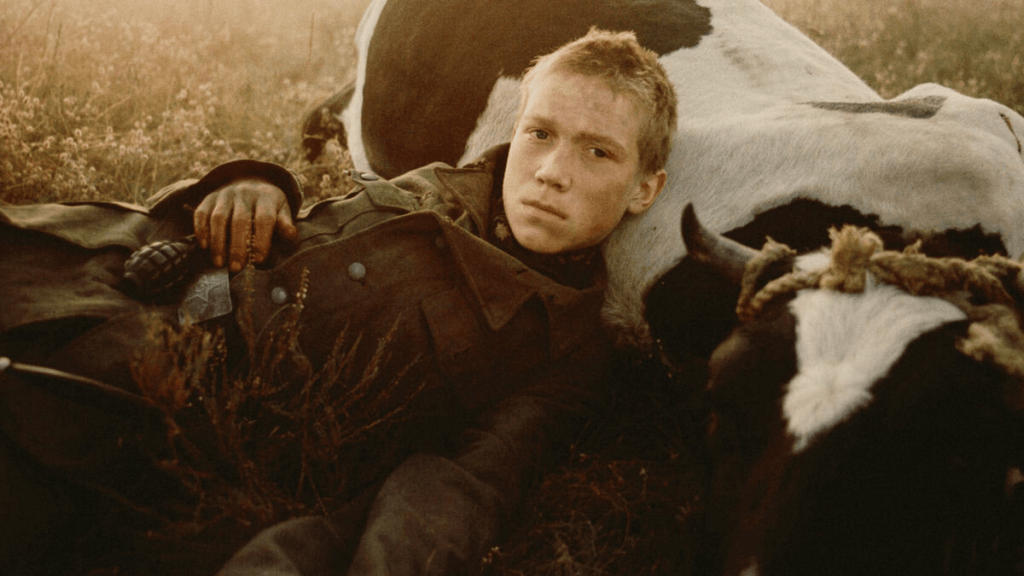

To watch Elem Klimov’s stunning anti-war film about a boy navigating the German occupation of Belorussian is to feel shattered again, and again, and still yet again. My heart breaks for Aleksei Kravchenko’s Flyora, from the opening moments when he excitedly grins his way into the partisan resistance, completely naive to what’s coming, to the final scenes where his face bears the weight of unimaginable horrors.

There is a a delirium to Come and See that echoes Kon Ichikawa’s 1959 Fires on the Plain and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Apocalypse Now, and it’s easy to see why the format is so effective. War’s incomprehensible savageness is transformative of the people and places it consumes, and the inescapable air of death is suffocating—when Flyora and the young woman Glasha share moments of laughter and dancing in the forest the feeling of tranquility is matched by dread and unease. These characters may find a momentary escape, but Hell is always just around the corner, whether it’s in the German reconnaissance aircraft that’s always soaring above, a sudden artillery strike, or a mobile death squad looking for its next massacre.

These scenes are done brilliantly through painfully intimate close-ups, long takes, and slow pans that create a harrowing all-encompassing feel. Every sequence carries a searing realism that haunts the imagination, from the viscous bog that Flyora desperately trudges through in search of his family, to the images of Nazi death squads descending on a town with fire and machine guns. And the use of sound and music is of particular note, especially when Flyora temporarily loses his hearing for part of the film—the world around him is dampened save for muffled voices and discordant notes that could’ve originated in a horror film. Occasional, brief inserts of pre-war music act like broken pieces of memory tossed around inside Flyora’s head, one of my favorite details.

It’s a tremendous project, and to hear of the film’s historical accuracies after the fact is to feel defeated all over again, yet wildly impressed at such an unflinching picture. I cannot imagine the process of creating it, especially when reading about the use of live ammunition and explosives on set; it is perhaps no wonder that Klimov never again made another film.

Leave a comment