This is a review of a Normal difficulty playthrough of Death Stranding 2.

I mention this specifically because I suspect a lot of players who really enjoyed the tedious-by-design step-by-step delivery process of the first game will have a better time with the sequel’s Brutal difficulty. This is because Death Stranding 2’s Normal difficulty—the third highest of its four settings, by the way—feels noticeably smoothed over from what I remember the first game being like.

It’s a sentiment I’ve seen echoed in a few other places, that Death Stranding 2 is an overall easier and kinder game and that the things that made Kojima Productions’ debut frustrating were also the very things that made it so interesting, and perhaps Death Stranding 2 is less interesting as a result of its sanded-down edges. And the truth is that in the 45 or so hours I spent completing it, Death Stranding 2 was not difficult at any point. I only died once, not because of a encounter but because I recklessly drove a truck into an enemy base for the hell of it, and the vast, vast majority of deliveries I completed were granted an S or A rank due to the impeccable quality of the cargo upon receipt.

At the same time, Death Stranding 2’s story is significantly less plodding and over-explanatory than the first, so watching the game’s narrative play out is, much like the gameplay, far less of a chore than it was before. Whether or not these sound good to you will likely depend on your lasting impression of Death Stranding and it’s unique brand of weirdness. But across the board this is a better-playing and better-written—maybe not exactly well-written, but better–written—game.

With most of its glacial world-building out of the way, Kojima is able to get down to business in Death Stranding 2. Sam Porter Bridges (Norman Reedus, as grim and distant as ever) is living in retirement in a bunker in Mexico with his child Lou when he is visited by Fragile (Lea Seydoux, as unfortunately—or intentionally?—monotone as ever) who recruits him into connecting Mexico to the chiral network—the nebulous all-powerful communications platform that effectively brings isolated human settlements online, linking them together through communication, manufacturing and instantaneous data transfers by way of an otherworldly (but accessible) purgatory called the Beach. It’s a critical element of this post-Stranding world. Without a link to the chiral network, a settlement may as well be lost to the winds.

One thing leads to another, though, and Sam finds himself in Australia of all places to perform the same task he previously carried out in the former United States on behalf of the fledgling UCA government: bring an entire continent online. He is decidedly less alone this time around. Fragile, no longer associated with her Fragile Express delivery company, is now a part of Drawbridge, a private organization that seeks to expand the chiral network without any direct affiliation with the UCA, a tactic meant to assuage the skeptics who might be wary of a foreign political body instituting its own communications network in another country.

Sam and his companions travel aboard the DHV Magellan, a ship capable of riding the tar currents that swim beneath the earth. It’s one of the game’s cooler concepts, this Metal Gear-looking transport that slinks beneath the soil and rises again in a new location, floating and rotating above the ground with a melody sounding over its exterior loudspeakers.

Unlike the first game, which saw Sam mostly on his own, only encountering the supporting cast in their own outposts, there’s a crew along for the ride. You don’t see them outside of cutscenes, but you do return to the Magellan constantly to rest and debrief with the cast. At first, Death Stranding 2 appeared to be repeating some of the narrative mistakes of its predecessor by hitting you with some bafflingly strange characters with the most bizarre traits—a doll that houses a man’s soul and animates at a lower frame rate, a captain whose severed hand floats in the tar and acts as a navigation beacon for the Magellan, an infinitely pregnant woman who seemingly conjures rain that reverses the effects of Timefall… you know, the rain in Death Stranding that rapidly ages anything it touches. You meet these characters and then their respective cutscenes just end, with nary a hint of confusion or wonderment on Sam’s face, as if we’re all just meant to accept that these are completely normal people to exist. And the thing is, once you’re fully in on Death Stranding, this cast becomes a curious delight and one of the highlights of the game. It’s a refreshing change for Sam to have a team with him.

The same cannot be said for the dozens of characters who inhabit the game’s settlements and outposts, who are mostly one-note hologram cheerleaders for Sam on his journey. They speak in the same plainly positive tone and have very few identifiable traits other than the ones they exhaustively explain to you, should you question them about it. This is where Kojima uses his a lot of his celebrity facial scans (but not their voices, so be prepared to see recognizable faces speaking with Australian accents).

The game’s primary antagonist is also a let-down. Higgs is back and continues to be an empty vessel of a character. Troy Baker’s performance is absolutely terrific and he really chews through the scenery in this game, but it never feels like Higgs has any meaningful driving force, no clear cut goal or ambition that might inspire Sam to fight for something. His role in the story does little to expand our understanding or appreciation of this world and the characters in it. Higgs shows up unexpectedly, you fight him, he goes away, and a dozen or so hours later it happens again, only this time he’s gotten a bit more smarmy. That being said, the rivalry between Sam and Higgs, such as it is, culminates in one of the most riotously funny and unbelievable sequences this side of the Metal Gear Solid series, so I suppose that’s something to be thankful for.

In a general sense, while I do think the writing in Death Stranding 2 is improved over the first game, there is still an underlying irritation with the game’s decision to over-explain some things and leave other things totally opaque. There is a mostly helpful in-game codex that explains many of the game’s concepts, but that doesn’t make it any less weird how often something inexplicably ridiculous will happen in a cutscene, followed by a settler hologram needlessly explaining what happens when you attach a battery pack to your vehicle immediately after an unmissable tooltip did just that, or a character suddenly explaining what a brinicle is as if he’s reading from the Wikipedia page. It’s pretty clear there’s a division between Kojima’s desire for mystery in his stories, leaving some things unexplained like the illustrious, imaginative filmmakers who certainly inspired him, and a desire for the gameplay side of things to be as comprehensive and unambiguous as possible.

Going along with the ride is for sure the best way to enjoy this world, and I did really enjoy some of the out-of-left-field moments that crop up. Sudden music performances, unexpected fast travel mechanics, the high volume of thumbs-ups that characters give each other, all of these contribute to a game that delights in little surprises here and there. It’s a sci-fi world that can be bizarrely engaging when it’s not annoying, and Death Stranding 2 is certainly less annoying than the first game. Its cutscenes are well-directed too, with some terrific shots that make it clear there’s a cinephile directing this story.

One of the story’s strengths is its pacing. After major events you almost always get a nice cooldown period where the game encourages you to move to a new area and explore. Rarely do you experience that open-world trope of constant emergencies happening, but hold on a second, I need to complete a bunch of side quests first. I settled into a nice groove of completing side deliveries until I felt ready to move on to the next story beat, after which I would return to my porter work again, and repeat.

Death Stranding 2’s cargo-hauling is just as satisfying as it was the first time around, and there are a ton of quality-of-life features, both new and improved, that make the experience quite seamless. Auto-sorting and moving cargo between your backpack, a vehicle, your hands, or the ground is fast and easy. Certain situations that might require a ton of menu navigation are helpfully shortened with smart menu design—if you’re trying to fabricate some equipment but the facility doesn’t have enough resources in stock for it, the game will automatically pull up some items you have that you can recycle to get the exact right amount of materials that you need, taking out the guesswork and back-and-forth menu bouncing.

Not everything is made super clear. I didn’t really understand how to use monorails or mines until I was nearly finished with the game. There are a few different fast travel mechanics that have some restrictions on cargo coming with you, which was just confusing and limiting enough that I mostly didn’t bother with fast travel at all. The rules around getting separated from your cargo can also be unclear. You can remove your backpack, which is very helpful in combat so you aren’t stumbling around with a stack of crates during battle, but the game frequently hits you with messages about cargo you apparently lost or got separated from getting assigned to other players, so I was always nervous to leave anything on the ground lest it disappear. The game also likes to flash red icons on cargo related to orders as soon as you aren’t carrying it, as if its an emergency that you’re leaving it behind, or perhaps it might explode. It was hard to tell.

None of this was particularly troubling considering how difficult it must be from a design perspective to keep all of Death Stranding’s various ducks in a row, and to make the experience as friendly and usable as it ultimately is. But I would’ve liked to have a better handle on these systems so that I could feel more confident playing.

Overall, though, confidence was the trait I lacked the least in Death Stranding 2, and that’s because for as hostile as the game wanted me to think its world was, the actual experience of getting around it was anything but unforgiving. Vehicles are king in Death Stranding 2 and you can take them just about anywhere. Even when the game warns you about rough terrain up ahead, and that you should pack some mountaineering tools, you almost never need to. When I reached the snowy peaks in the back half of the game, which promised to be the toughest navigational challenge yet, I immediately drove a motorcycle straight up the slopes with zero trouble. When I reached the very highest peaks the game warned me to watch my oxygen levels due to the high altitude, a mechanic that never actually affected anything for me in part because I was given an oxygen mask to completely nullify it right away. The lower-level terrain isn’t particularly challenging either, because again, you can just take a truck or motorcycle over everything in this game. The single hardest thing about navigating Death Stranding 2 is trying to decipher the in-game map, filled as it is with tiny lightly-colored icons that are nearly impossible to distinguish from one another.

The sheer number of tools and environmental warnings in the game about temperature and high water levels suggests a harsher world to traverse than what’s actually there. And comically, the ease of travel actually undermines Death Stranding’s favorite trick of kicking in a song and pulling the camera back as you near your next story destination—there were a handful of times where I was zooming along so quickly that I reached my objective, and thus ended the song, before the first verse had even begun, totally defeating the moment.

And of course, once you connect a settlement to the chiral network, the game populates your world with structures from other players that further ease the burden. Zip lines, generators, highways and the like spring to life, a feature that is still as excellent as it was in the first game, but that isn’t quite as impactful as it would be if getting around was more of a chore in the first place.

There is a general feeling in Death Stranding 2 that a lot of its equipment and structures are either unnecessary or only utilized in hyper specific use cases that never come up. I only used ladders and climbing anchors maybe a couple times each. I tried out the cargo cannon structure once and it was utterly pointless. You can tie your cargo together with a cord, a feature I forgot about for my entire playthrough. I only bothered with one type of exoskeleton and never once used a BT capture grenade that you can use to capture and summon a BT in combat, or something. There is a lot of stuff to play with in the game but you might only need about 20% of it.

There is still exciting game-changing stuff to acquire through ranking up the different settlement outposts. Each outpost (I never know what to call them. Outposts? Preppers? Survivors?) can be ranked up to five stars, with each star granting a new unlock or upgrade. Helpfully, a lot of the early unlocks at these outposts are useful right away, so it never feels like you need to grind out deliveries in order to get some good equipment.

Death Stranding 2 has quite a bit more combat than its predecessor and it’s a tad bit better, but the act of engaging enemies in gunfights still feels like its been shoehorned in to a game that’s primarily about running around peacefully. There’s less of a distinction made between human enemies and BTs this time around in terms of the weapons you should use, since any weapon labeled [MP]—which is most of them—will work against both. Hostiles are located around the map in areas that are helpfully denoted on the map, so it’s never a surprise when you encounter them.

The combat overall is remarkably easy on Normal difficulty, including the boss fights against giant enemies that I dreaded so much in the first game. These boss fights require little of you beyond standing in place and shooting the glowy bits until it’s over. Combat against bandits and BTs is much the same—just point and shoot and you win without much hassle. I was never close to expiring at any point, save for the one aforementioned death when I yee-hawed my truck, equipped with an auto-targeting machine gun and mortar launcher, into an enemy encampment and one of my foes managed to land a grenade or some other explosive underneath me.

Similarly to the game’s overabundance of tools and structures you probably don’t need, there’s a lot of easily-ignorable overcomplicating mechanics in the combat. The game wants you to think that melee combat is a core component, but I didn’t throw a single punch in my playthrough. If you kill an enemy you have to dispose of their body, but I never had to do this because you really have to go out of your way to dispatch someone lethally. And any time the game warned me that an upcoming battle was going to be tough because the enemies had upgraded their armor, and I should really think carefully about my approach and the equipment I bring, I did not think carefully about it at all, and went in with the same guns-blazing tactic that proved to have a 100% success rate in all fights.

I wonder how much the experience might change on Brutal difficulty, which I never tried in my playthrough. Somehow there are two easier difficulties than Normal, which is wild consider how straightforward and painless Normal is. Might there be more incentive to engage with the game’s various tools, combat options, and structures on the harder choice? That’ll be for others to figure out, or myself if a second playthrough comes my way down the line.

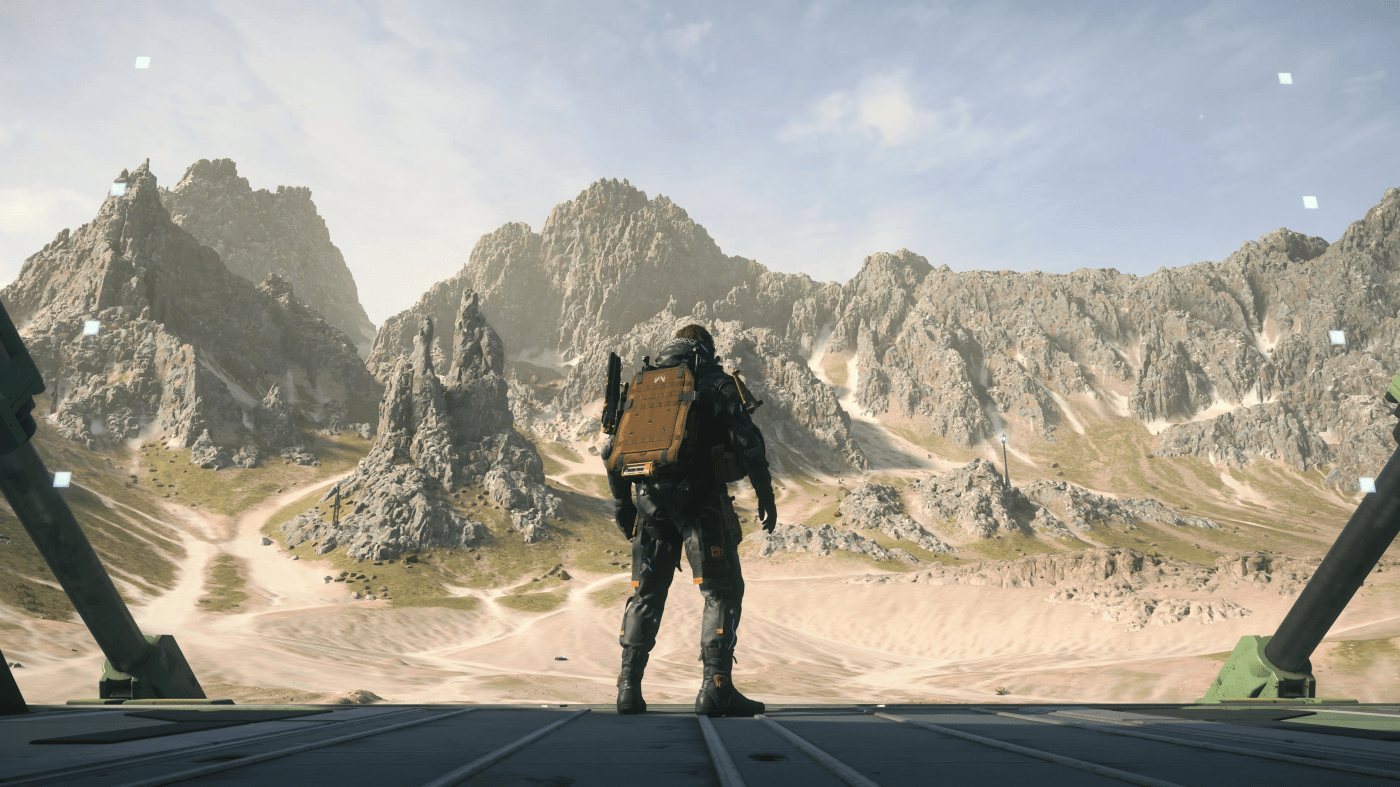

What really sells the journey in Death Stranding 2 is the game’s unbelievable visuals and sound design. This may well be the most realistic-looking environment I’ve seen in a video game. It’s frequently breathtaking, from the very first moments standing atop some rocky crags in Mexico, to traipsing up and down snowy mountains in Australia. The level of detail is outstanding, and I especially loved the way sunlight diffuses through clouds and bathes mountain faces in warm golden hour hues. If you’ve ever enjoyed a stunning sunrise or sunset, either over water or on a peak, Death Stranding 2 will instantly take you back to those moments over and over.

It’s that classic feeling of a video game world that’s alive, made all the more real by other details like Sam getting sunburns and frostbite after enduring a harsh climate, or collapsing to his knees for a moment after an arduous trek through snow or a lengthy battle that depleted his stamina. And it all sounds incredible too—wind blowing through the peaks, pattering rain, the mechanical whirring of an exoskeleton, all the little plings and beeps and melodies and stingers that play when passing over signs left by other players or receiving a codec call from the team aboard the Magellan. It’s all just brimming with little bits of life that make every moment of the game feel tactile and lively.

What are we left with then? A sequel that largely smoothes over some of the more agonizing aspects of the first, and how you receive that will depend on what you’re looking for. If a challenge is what you seek, anything below Brutal difficulty will not satisfy. If a smoother ride is the goal, Death Stranding 2 feels designed for you. It still has a lot to offer: a stunningly-realized sci-fi world with spectacular views, intricate gameplay systems that are largely friendly and satisfying, just an overall tone and structure that feels totally unique, a gem of creativity within the AAA space that can feel so risk-averse these days.

The game might’ve benefited from trimming down some of its mechanics and really honing in on a core selection that it could incentivize players to use more. I think Death Stranding 2 would’ve been a more exciting game if more of my delivery routes required something from me, whether it be careful navigation or creative deployment of tools and equipment. But maybe that ends up being a hundred hour game, and instead Kojima Productions chose to let players decide how much of the nitty-gritty they want to interact with. I’m not confident this is always the best design decision—I tend to think that games are almost always better when players are encouraged to use all available tools and resources, rather than ignoring most of them. But this open-ended, use-it-if-you-want approach might be exactly what the game needs if Kojima and co wish to broaden its appeal. Whether or not that is a good thing is another matter of debate.

Leave a comment